FOUR PHASES OF CULTURE

- iamjamesdazell

- Aug 3, 2025

- 35 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2025

A James Dazell Theory

🌑🌒🌓🌔🌕🌖🌗🌘🌑

“Every new beginning comes from some other beginning’s end”

Lucius Annaeus Seneca

PREMISE

Culture is the proposal for a solution to the living aspect of the human experience of existence.

Art is the preservation of the disposition of that proposal as an experience.

Religion is a kind of conceptual thought to make the human experience more agreeable.

THE THEORY

This theory came to me when I asked myself “what’s the first thing to arise in a culture?”

History of art has long found parallels across cultures. The archaic Greek style and the Early Renaissance are austere. The Classical and High Renaissance are harmonious. The Hellenistic and Baroque style are full of expressive emotional drama. But this is always regarding visual art, and doesn’t assess culture in a more holistic sense.

Just as the moon cycles through five phases, and as the sun sets it also rises somewhere else in the world, cultures turn through phases; die in one way and are born again in another.

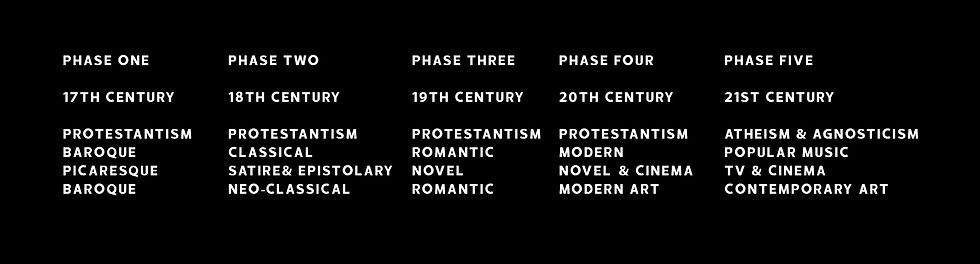

My Four Phases of Culture theory proposes that cultural periods transition cyclically through four dominant phases in the order of — Religion, Music, Literature, and Images — each one discovering innovative methods and forms of expression which embody the original sentiments of the religious disposition which inaugurated the cycle. (I’ll discuss the reasoning for these broad labels later).

The beginning of a cultural period is inaugurated by a shift of religious perspective, and ends with a phase of a great saturation of visual expression which embodies the ideals of that inauguration.

1. The first phase is a change of religion, which presents a new conceptual or metaphysical perspective and disposition. This is more than a shift in philosophical temperament. Religion provides the initial and foundational architecture for understanding existence. It answers the metaphysical questions through order, myth, ritual, and ethical frameworks that stabilises a cultural worldview.

2. The second is music, born out of the shift of religious disposition that finds innovative means to express itself. Music, after all, is the preservation of a disposition towards life. Music is a kind of metaphysical relationship between oneself and life, evoking the metaphysical disposition of the corresponding inaugural religion, which you experience through either listening to or playing music. A metaphysical disposition which is emotionally felt but unarticulated.

3. The third phase is literature, which begins to articulate that disposition on a human level as opposed to a metaphysical level. The sentiments of the metaphysical disposition are articulated in the more familiar human experience. Yet a version of the human experience that weaves in the ideals and values of the religion, embedded into that literature. The way we experience something in the memory is selective rather than in totality. Our memory is itself a story-teller. Storytelling is a way not just to recall a memory but invent experiences. Experiences which help define a community through a shared worldview. It takes those religious values, and the metaphysical disposition, and presents them as a lived experience.

4. The fourth phase is images, which is the final phase of a culture period. When there is a heightened era of visual imagery that predominates a culture, it’s basically summarizing of the previous three phases of religion, music, and literature, now visually articulated as a frozen image. In a sense, it's the most superficial and derivative phase, because it’s basically possible because so much has already been accomplished, and the images are essentially a visual projection of the previous three phases. Yet in another sense, it is the most marvellous because it is the actualisation of the cultural period. It embodies all of the meaning of the previous phases. Simultaneously, it is the climax of a cultural period, whilst also signifies its decline, because it also marks the point of saturation of the cultural period’s ideals, which have now been expressed with enormous variation. What comes after the phase of images is, of course, a new religious phase.

Each phase builds upon the previous, refining and innovating to achieve further expression of the same sentiments and disposition. Each one reaching greater fulfilment of the ideals of the religious phase. Each expanding cumulatively and interdependently, or even derivatively, upon the previous. The religious shift is not only the root of meaning but also the original composition of what later arts will pursue actualising.

There is arguably a fifth phase, which is the disillusionment and breakdown of the ideals of the cultural period. But this phase is rather an undercurrent than a phase in itself, as its the impetus for the shift in religion which starts the cycle all over again. So, it’s really part of the first phase that proposes a new idea. I believe we are currently in the fifth phase. We are in an era of image saturation, disillusionment, and the breakdown of Modern ideals. Although we like to think we live in an atheistic secular society, I don’t believe the politics of our time suggests that. The twenty-first century has retrogressive religious attitudes that seem to want to pull us back into the medieval era. The history of this century and the next may enter a new religious phase that inaugurates a new cultural period that leaves the Modern era behind. Every new cultural cycle begins in a condition of disillusionment, but disillusionment alone does not generate a new metaphysics. What initiates Phase One is the moment when a small number of individuals find themselves living anachronistically inside a fading worldview: they still hold values that the present age no longer upholds, and they are compelled to seek a way of preserving those values while also surviving in a metaphysical climate no longer shaped for them. A new era begins because certain individuals or communities cannot continue in the world as it currently stands. Their interior loyalty to what they hold true becomes incompatible with the structure of the civilisation around them. The search for a new worldview is therefore an existential necessity. The task of these individuals is not to return, but to re-create — to forge a new structure capable of carrying forward what the old one could no longer sustain. Their work is neither dialectical nor restorative; it is generative. and transformational They inherit from the past the essence of what must survive, but the form they give it is necessarily new, because only a new form can succeed where the old has failed. They seek to produce something sufficiently resilient, sufficiently adaptive, to withstand the pressures that its predecessor could not survive.

This is why the founders of Phase One are never reactionaries. Buddha was not returning to the Vedic religion; he was creating a metaphysical alternative when the ritual structures of his society had reached exhaustion. Confucius was not reviving the Zhou order; he was rearticulating its core principles in a form that could endure political breakdown. Jesus was not restoring ancient Judaism; he was constructing a radically new cosmology that could preserve what he believed Judaism had lost. Luther was not returning to the early Church; he was reframing Christianity in a way that could survive the corruption and spiritual inertia of late medieval Catholicism. Aquinas was not restoring antiquity; he was integrating Aristotle into Christianity in a way that produced a metaphysics capable of generating the Renaissance, something the Ancient Rome failed to do.

In each case, the new metaphysics is a transcendence, not a restoration — shaped by the pressure of the time, the ruins of the old order, and the impulse to preserve something enduring by transforming it. The creator of Phase One stands neither as a guardian of the past nor as an architect of pure novelty, but as a figure who must hold fidelity to a principle while accepting that only a new structure can bear it forward. Their imagination is therefore both retrospective and visionary: they recognise what has been lost, but they do not cling to the old vessel; they design a new one, strong enough to cross the sea that shipwrecked the last.

This is why Phase One is always religious. Religion is the only cultural force capable of reordering the foundational architecture of meaning at a metaphysical level: it establishes a new cosmology, a new moral sensibility, a new temporal horizon, and a new emotional register. It offers not merely critique but a viable way of living. The figures who initiate Phase One are responding to the collapse of the previous metaphysics not simply with analysis, but with the construction of a new order in which their values can survive. Their work is protective, conserving, even salvific: it saves what the old world no longer supports. The ordinary population does not initiate this pivot. They do not philosophically examine metaphysics, or compare civilisations. They inhabit the present arrangement because it is what one does, the atmosphere into which they are born. The transformation of meaning always begins with a minority whose inner life no longer fits the existing metaphysical container. Their dissonance — their anachronism — forces them to seek a new form. Once articulated, this form is adopted by elites, institutions, and cultural centres, because it offers solutions to practical, political, or existential problems the old metaphysics can no longer solve. Only then does it filter into collective life, where it becomes the air of a new epoch.

Phase One is thus the birth of a new religious architecture, understood in the broadest anthropological sense: a system of meaning robust enough to sustain life after the collapse of the previous worldview. It arises from the crisis of anachronistic souls struggling to survive in a world whose metaphysics has reached exhaustion. And once this new architecture takes hold, it becomes the foundation upon which all subsequent phases — musical, literary, and visual — will build, until they too reach saturation and a new cycle must begin.

TERMINOLOGY

These terms for each phase are used broadly and loosely to accommodate different periods of time. The Greeks for instance had no word for religion, nor was their religious worldview dogmatic in the sense that we mean it of organised religions today. The word spiritual is insufficient for those less metaphysical. A worldview is closer, but it doesn’t imply the depth of a religious worldview, which is an entire conceptual framework of life.

As for Literature, any pre-literate societies didn’t write literature, and even those pre-oral tradition didn’t tell stories by language. So, the literature phase is really a kind of memory of the lived experience. Especially a shared or communal memory. A religious worldview expressed, not by the metaphysical but through the familiar human experience. Once writing is invented, the memory of lived experience can be recorded with greater creative complexity. Mankind thinks in images. The combination of music and memory would have only heightened those images. I’ve considered theatre and cinema as a literary arts in my categories because they are either born out of literary elements, as theatre, or they are a visual literacy as in cinema. But both are a presentation of an invented experience as collective memory. Visual art is more of a contemplative activity.

Images can refer both to figurative and geometrical images. Since the culmination of images in the Islamic world is geometrical, and even Judaism rejects idolatry in favour of abstraction. This makes the definition broader than painting and sculpture. The terms are broad, but ensure we’ve not lost our grip on a direct reference to the cultural arts.

ANCIENT GREECE

Let’s start with Mediterranean Antiquity of Ancient Greece (ca. 800 BCE–146 CE) as an example

PHASE ONE – RELIGION:

A revival and development of Mycenaean religion after the Dark Ages (1100-800BCE)

PHASE TWO – MUSIC:

Since poets were musicians. Homer develops through a long tradition of oral poetry. These epic poems are not just stories, but foundational cosmologies; they defined what the gods are, how fate functions, and how humans should behave in it. This musical phase is directly tied to religion. However, what also emerges is lyrical poetry, established in the 7th century BCE, expressing the personal and emotional sentiments. I would also put dance in this category in any period, since dance has always corresponded very directly to developments in music.

PHASE THREE – LITERATURE:

In this case I say literature loosely, because Ancient Greece didn’t have a literary culture in the way we think of it. But the 5th century BCE has significant developments in the writing of history and philosophy defines this as the literary phase, whilst Greek drama involves speech not only songs.

PHASE FOUR – IMAGES::

The procession of Ancient Greek artistic styles culminating in Hellenistic art, absorb the former phases into saturation. I’ve discussed this cultural period thoroughly in both my video on The Origin of Drama and my video of Ecstaticism.

Ancient Rome has a similar shift where it assimilated Ancient Greece’s religion and aesthetic culture into their own indigenous polytheistic religion and arts in the 3rd-4th Centuries BCE. Cultural periods are not defined by regional definitions, but by religious ones.

THE MIDDLE AGES

If we move to the European Middle Ages c. 300–1200). The Roman Empire covered over 50% of Europe at this time:

PHASE ONE – RELIGION:

Christianity becomes the official religion of the Roman Empire, from the Mediterranean to Britain, but also into North Africa and the Near East. So the impacts of cultural change are enormous. The Edict of Milan in 313 CE (under Constantine I) legalized Christianity. Later, in 380 CE, Emperor Theodosius I issued the Edict of Thessalonica, making Nicene Christianity the state religion of the Roman Empire. This shift began the transformation of the Roman spiritual landscape from a polytheistic to a monotheistic order. Pagan temples were repurposed; Christian theology infused imperial authority.

PHASE TWO – MUSIC:

Music of Gregorian chant and plainchant, developed between the 6th and 9th centuries; formally codified under Pope Gregory I (r. 590–604). Performed during the Divine Office and Mass, aimed to induce a meditative, otherworldly state, to facilitate divine contemplation. Art already begins to move away from classical realism to symbolic abstraction in service of transcendence.

PHASE THREE – LITERATURE:

Chivalric romances that rewrote the idea of ancient epics into tales that exemplify Christian ethics. For example, Chanson de Roland (c. 1100) — a tale of heroic sacrifice in service of God and empire. These stories reframe earlier pagan and heroic epics through Christian moral ideals: loyalty, humility, penance, divine justice. The knight becomes not only a warrior but a spiritual aspirant. The grail is a Eucharistic mystery. Love is courtly but ultimately meant to refine the soul towards moral improvement through acts of service. The portrayal of love in Western cinema arguably still portrays this Christian idea of love that was fashioned through the chivalric romances.

PHASE FOUR– IMAGES:

Iconographic Christian imagery of Constantinople. Whilst ancient Roman art emphasized naturalism, idealized human figures, and narrative scenes, displaying depth, perspective, anatomy, and emotional expression. Christian art became symbolic representations more focused on meaning than realism, moving increasingly towards abstraction. Gold backgrounds began to appear as symbols of divine light or the heavenly realm. Figures become more elongated, less grounded, with large, expressive eyes. Proportions serve theology, not optics. Focus shifted from worldly appearance to spiritual essence. These images were not meant to depict the world but to lift the mind to God. The visible pointed to the invisible.

What’s most interesting is not so much the transition from Classical Roman to Byzantine, but from Byzantine to Renaissance, and the return to naturalism. There were deeply held theological reasons for Medieval Christian art to be what it was. The shift from Medieval to Renaissance was a theological reframing of Christianity that began to accommodate views that it once resisted. The medieval era is mostly influenced by the views of St Augustine, and begins to change after the Islamic Empire expands into Spain. Europeans still read the Classical literature from antiquity throughout the Middle Ages, particularly in the reign of Charlamagne. So it’s not simply that people revived an interest in antiquity. I think more significantly was the shift from Neo-Platonist views to Aristotelian views, which very much came out of the commentaries and translations of Ancient Greek and Roman texts through the translation movement of the Islamic Empire.

Byzantine Iconoclasm refers to two periods of state-sponsored destruction or prohibition of religious images (icons) in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire. There were polarising views around the creation or prohibition of religious images between two groups Iconoclasts ("image-breakers") and the Iconodules ("image-venerators").

Iconoclasts had Theological Concerns:

The commandment against graven images (Exodus 20:4) was taken literally.

Critics (iconoclasts) argued that worshipping or venerating images was idolatry.

They believed Christ's divine nature couldn’t be captured in matter without diminishing it.

The defence of iconoclasm often drew on Neoplatonic ideas: the material world is inferior to the spiritual.

Whereas Iconodules supported the use of icons, not as idols but as windows into the divine. Believed that because Christ had taken on flesh, his image could be depicted.

The first iconoclasm (726–787) ended at the Second Council of Nicaea (787 CE), which affirmed the veneration (not worship) of icons as orthodox. In the Second Iconoclasm: 814–843, the icon became a formalized, stable type. Artists followed rigid templates rather than innovate. Artists now signed their works less often, reinforcing the idea that the icon was not “art” in the human sense but a sacred conduit. The influence of ascetic monasticism (especially Athos) meant art was to deny the world, not represent it. Gold backgrounds, elongated limbs, large, soul-penetrating eyes — all to convey spiritual presence, not likeness. Perspective was eliminated: the space was timeless, spiritual, non-earthly. Figures became even more flattened, frontal, and symmetrical.

Neoplatonism was the philosophical anchor on Christian art, especially through Augustine (354–430 CE). A distrust of material reality, ideal forms, inner vision, with an emphasis on transcendental spiritual ascent. A reintroduction of Aristotle’s works, through Arab-Latin translations and commentaries, were entering Europe. This is where Aristotle begins to displace Plato in terms of influence — and this shift sets up the Renaissance. Culture is always better whenever it favours Aristotle over Plato.

After the influence of new commentaries on classical texts, arguments around art began to shift. Saint Francis of Assisi (1181–1226 CE) emphasized the humanity of Christ, nature, empathy, and visual storytelling in the vernacular. Later, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274 CE) argued all things, including material bodies, are created by God and reflect God’s goodness. Not only matter not evil, but sensory perception, beauty, and nature are valid ways to know God. Aquinas argued that God became human in Christ, and this incarnation dignified human nature permanently. This provided theological justification for art that portrayed Christ in human terms — with sorrow, tenderness, flesh, proportion, and realism. This validated the human body as a worthy subject of spiritual reflection — even in visual art.

“It is lawful to have images in churches... in order to instruct the ignorant and to stir up devotion.”

— Summa Theologiae, III, q. 25, a. 3

In line with this theological emphasis on emotional narrative realism in painting, artists began showing the human suffering of Christ and compassion of Mary—not just divine triumph.

Cimabue (c. 1240–1302) still worked in a Byzantine tradition, introduces more emotion in facial expressions, slight naturalism in drapery and body under cloth, and a sense of space and mass. Later, Giotto (c. 1267–1337) eclipsed Cimabue, making a bold leap forward. Giotto’s re-introduces narrative drama and emotion, his figures have volume and weight, human gestures and faces begin to replace the distant stasis of Byzantine art, and his scenes are set in shallow but recognisable space.

THE RENAISSANCE

PHASE ONE – RELIGION:

The Islamic usurpation of the barbarian Visigothic Kingdom, present day Spain and Portugal, is the catalyst towards the Renaissance.

The effect of Christianity of Europe, and the fall of the Western Roman Empire, was not quite paralytic on European culture, but it was retrogressive, with the exception of France particularly under Charlamagne. Muslims from the North African Islamic Empire, didn’t invade and conquer Spain in the 8th century as is often said. A Visigothic King, hired Muslim mercenary soldiers to fight off the various Germanic tribes that were in internal divisions for power, hoping to claim greater power for himself. But, as Machiavelli wonderfully articulates, you come to ruin if you hire mercenary solders because they’re disloyal, and if you hire auxiliary troops, because they are more powerful than you. So the Muslim troops were disloyal and proceeded to takeover region by region. However, Fate had a secret blessing for Europe, because otherwise the most glowing light of the past two millennia might never have happened. The Muslims had acquired lots of ancient Greek and Roman texts from the Byzantine empire, and brought them to Europe, and wrote commentaries on it, building upon this ancient knowledge. Toledo was a particularly significant region of learning, and the seat of the translation movement from Arabic to Latin, many of whom were Christian translators. The erotic poems of the empire, influenced the French love songs of the troubadours, which influenced the Italian sonnets of Petrarch, which influenced the sonnets of Shakespeare. Even the architectural splendour of Islamic temples gave inspiration to the Italians to resume the architectural elegance of Ancient Rome. And even hired Muslim architects to help build Italian churches. All of this is a shift away from a conservative Christian Europe towards a syncretism of Greco-Roman ideas into Christianity, which develops into Humanism.

The Black Death (1346-1353) which killed over 50% of Europe’s population, intensified Humanism because Europeans became disillusioned with medieval ideals of religious devotion. It brought a heightened awareness and reflection of the mortality of the physical body, and the temporary pleasure afforded in being alive. If Culture is the proposal for a solution to the living aspect of the human experience of existence, then the ideals of the medieval era were no longer sufficient. This is phase five which coexists with phase one of the subsequent culture.

PHASE TWO – MUSIC:

The music of the Renaissance is often incorrectly paired with composers like Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina or even Jacopo Peri. But they don’t represent the spirit of the Renaissance at all. The music of the Renaissance was the music that’s often considered as part of Medieval period. The music of the medieval era is largely plainchant. Meanwhile there is a new music movement flourishes across Europe with the Cantigas of Alfonso X, School of Notre-Dame, the Goliards, the Troubadours, the Sicilian School, the Florentine trecento, stimulated by the religious shift and the introduction of Islamic love poetry.

PHASE THREE – LITERATURE:

There are more signs of Roman antiquity in the 14th century than in the 16th. In the 1300s you have just in Florence alone, the painter Giotto; the poets and writers Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio; the sculptor Donatello; composers Francesco Landini and Gherardello da Firenze, and even the architect Brunelleschi was born in 1377.

PHASE FOUR - IMAGES:

What is traditionally considered the peak of the Renaissance, known as the High Renaissance which is often considered to be the 16th century, comprising of the work of Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, Rafael, actually represents the declining era of that cultural period, which in hindsight obviously was, since its when the Renaissance ends. Whilst the early Renaissance was driven on a revival of Aristotelian views, the High Renaissance through thinkers like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pica de Mirandola, revived a Neo-Platonist view. So the High Renaissance was a Neo-Platonic revival. We traditionally view the Renaissance through the eyes of Giorgio Vasari – the father of art history. A mediocre 16th century Renaissance painter whose ideal artist was Michelangelo. Machiavelli collaborated with Leonardo da Vinci on a mission to divert the Arno River in an attempt to subdue the city of Pisa. To Giorgio Vasari writing in the mid-16th century, it was considered the establishment of a new golden age that had surpassed antiquity. Whereas a political theorist like Machiavelli, writing in the early 16th century he had very few positive things to say about his time. Both Florentine writers; according to Vasari, the ideals of the age were established. Yet to Machiavelli the country was in ruins. Machiavelli ushers towards Modernity. Machiavelli anticipates Modernity, but he is still part of the Renaissance cultural period because he is thinking about Ancient Rome and therefore still embodying the cultural aspirations of the period, which unlike Vasari, Machiavelli does not feel have been actualised. Whilst Giorgio Vasari is part of the fourth phase, Machiavelli is part of the fifth.

Phase Five might be the most interesting part to be in. It’s when you’re not derivative of anything but are challenging everything. In, 1517, Martin Luther nails the 95 Theses to the door of Castle Church in Wittenberg, Germany. Luther's actions spark the Protestant Reformation, challenging the authority of the Catholic Church and leading to a wave of protests and reforms across Europe. In 1545, the Catholic Church responds with the Council of Trent that marks the beginning of the Counter-Reformation. In response to the Protestant Reformation's emphasis on simplicity and the rejection of elaborate church decorations, the Catholic Church launched a concerted effort to promote and create art that would reaffirm Catholic doctrine and values, which could emotionally move the masses. This essentially revives an Aristotelian view: catharsis, ethical dramatization, sensorial engagement. Personally, I think the Baroque period, which is also part of the Phase Five disillusionment of the Renaissance ideals, was the greatest cultural phase of the Modern period. In 1618, two Catholic officials were thrown out of a window by Protestant nobles, sparking the Bohemian Revolt and the beginning of the Thirty Years War (1618-1648) as Protestant and Catholic forces clash. Creating sovereign nation states, and a Protestant Catholic divide between Northern and Southern Europe. The subsequent Enlightenment consisted of those who could not live under the realist perspective of the Baroque and formed new ideals based on the religious inauguration of this Modern period, wherein Moral Reason was attempted to solve all problems, with the naïve aspiration that by Reason alone the world would incrementally improve. The Baroque saw people exactly as they were, understood life as it was, and simply accepted it. The Renaissance writers of Machiavelli, Montaigne, Cervantes, Shakespeare, all informed the Baroque Period’s realists, such as Francois de la Rochefoucauld, Baltasar Gracian, and Ninon de L’Enclos.

MODERNITY

Then we enter into our own cultural period of Modernity.

PHASE ONE – RELIGION:

In 1517, Martin Luther sparks the Protestant Reformation. In 1534, King Henry VIII of England breaks away from the Catholic Church and establishes the Church of England, with the monarch as its head, England becomes a Protestant nation. The spread of Calvinism in the Holy Roman Empire created tensions between Calvinist and Lutheran states, as well as between Calvinists and Catholics. Martin Luther is the catalyst to the Modern period culminating in the cultural hegemony of the most Protestant country there ever was in history: The United States. Remember, it’s not region, but religion that stimulates cultural periods.

PHASE TWO – MUSIC:

Classical music is a total anomaly in the history of music. What’s so strange about it is its artificiality. It tries to articulate itself emotionally, it tries to dramatize the subjective emotional landscape, it tries to evoke imagery, above all, it tries to become drama. It’s not pure music. The late medieval music I already said was the impetus for the Renaissance, I think was the greatest music of the past two millennia, which only has world music of today to compete with. No one can deny how intellectually complex Classical music is. And also pleasant to listen to in many cases. However, it's an anomaly in the history of music. It's amazing and it's wonderful that music went there. But it's as if it's music that's not behaving as itself, but trying to behave like other arts of literature and visual art. Opera was invented at a time the influence of the medieval music had waned and church music was becoming the interest again away from the secular music of the early Renaissance. Whilst simultaneously the madrigal had innovated its attempt to not just play a music behind the lyric, but that all the composition of the vocal and the music should evoke the sentiments of the lyric. To me, this is an artistic mistake. To evoke the sentiments of the lyric is unnecessary because the lyric is already accomplishing that. For the music to pursue that is for the music to become literature. Preceding opera there were already great music dramas such as Adam de la Halle's Le Jeu de Robin et Marion, and the liturgical drama the Play of Daniel. Opera was invented with the idea that music should be, not pure music in itself for the pleasure of its own sound, but should be evocative of its lyrical sentiments. Subsequently once the German composers usurped Opera from the Italians, the idea of opera through, particularly Gluck and Wagner, was that everything was to be subservient to drama. This is largely the argument Nietzsche makes in his essay Nietzsche Contra Wagner. But I also discussed this idea of music in my video on Generation Y, as I think music is always best when it does the exact opposite. When the music expresses the opposite sentiments to the lyric so that the lyric can be expressed without emotional gravity, and the music can redeem it. As I mentioned in my video on Ecstaticism, I think the music of Spain – which by the way has its own form of opera called Zarzuela – was the more ecstatic music through the modern era of Europe until we reach popular music of the 20th century, which of course was largely indebted to West African music. There is no rock n roll, blues, gospel, soul, or jazz without West African music.

PHASE THREE -– LITERATURE:

The novel developed through Protestantism characteristics. Through the use of the printing press, illuminated manuscripts became obsolete and illustrated books became something gradually considered for children. Since the novel developed through both Protestant moral ethics and out of the literary style of the epistolary novel, the parable, and the picaresque, what began as a largely comedic or satiric form of writing, gradually turned on its head. The style of prose applied to the novel derives, not slightly from the epic but from comedy. Yet the comic perspective was displaced by compassion. A novel became a comedy we have pity for. The novel became the most hegemonic form of art I’ve ever known. If you enter a bookshop to find creative writing, if you ignore a small poetry and drama section, there is only one option: a novel. A novel is a very particular literary composition – which I think no longer suits our time – but agents, publishers, bookshops don’t print, publish, or present anything else. The Russian Golden Age writers perfected it, and at least the Modernist writers tried to mess around with it. I don’t think it has any life any more. I think it’s old fashioned in the way of opera.

PHASE FOUR– IMAGES:

Regarding Modern Art, in art we no longer have myth. Protestant iconoclasm stripped religious art of its mythic scaffolding, leaving a space filled by consciousness, and the ordinary. This is a break from every previous epoch: Classical, Medieval, Renaissance, Baroque art—all are steeped in mythological or religious imagery. Modern art is non-mythic. Modern heightened a subjective vision and a more biographical portrait, combined with the development of art history as an academic field, emphasised the artist as individual, and therefore the autonomy of the artwork. After an increasing pursuit of emotional subjectivity, Modern Art reaches the full realisation of the iconoclastic sentiment. Art finally rejects representation altogether —Abstracted from ritual or mythic reference (images no longer represent gods, saints, or stories), Often constructed around absence, alienation, or personal memory. Autobiographically subjective, existential, and psychological. Art attains aesthetic autonomy, rather than commissioned to be used for a purpose. Emphasises individualism of the artist as presenting a subjective individual vision, rather than presenting universalisms of myth or literature.

Art always criticises the art of the past in order to defend its direction. In Ancient and Renaissance art, it was not the figurative or naturalistic that is the point, but that it was a mythic art. Increasingly through the modern period, through Neoclassicalism and Romanticism, though it retained this naturalistic figurative style, it ceases to be a mythic art and instead was a form of portraiture. I've already talked about the incorrect perception of ancient figurative art as naturalistic in my video on the origin of drama and they've already written about existentialism in my video on Ecstaticism. Though there are many Modern Art examples of myth. It continues a hangover of the Renaissance idea of the absorbing the Greco-Roman past with Christianity, yet without aspiration towards imitation of antiquity. The myths are re-represented within the Christian framework, humanised with naturalism, but de-regionalised from their Mediterranean origin into representations of the Northern European.

The abstraction from naturalism, colours used for symbolic purpose, rejection of worldly illusion in favour of spiritual inwardness, rejection of perspective in favour of preferential treatment of scale, I’m actually talking about Medieval art, but could just as much be said of Modern Art. In fact there is an interesting parallel between the Medieval and the Modern.

There's an interesting parallel between the Counter-Reformation Movement of the early Baroque period and the Byzantine Iconoclasm Dispute of the Middle Ages. Byzantine Iconoclasm (726–843 CE).

Protestant Reformers | Counter-Reformation Catholics |

Rejected religious imagery (esp. Calvinists, Zwinglians). | Defended imagery to inspire devotion and teach doctrine. |

Favoured textuality, preaching, and iconoclasm. | Supported grand, sensual, and baroque visuality as a response to Protestant severity. |

Emphasized sola scriptura and personal faith. | Reaffirmed ritual, sacramentality, and the church's visual traditions. |

Byzantine Iconography | Modern Art |

Rejection of illusionistic space | Rejection of Renaissance perspective |

Use of colour symbolically (e.g. gold = divinity) | Fauvism, Expressionism, Kandinsky’s spiritual colour theory |

Frontal, stylized figures | Cubism, Primitivism |

Art as a spiritual tool, not entertainment | Malevich, Mondrian, Rothko: art as transcendence |

Standardized forms | Repetition of motifs in abstraction and minimalism |

Viewer contemplates icon to encounter divine | Modern viewer is invited into subjective or existential response |

Art can only glorify. It cannot deny. It cannot even reason. Whatever it presents it affirms. Art is a kind of yes to life. But what life means within that is dependent on the inaugural religious shift that the work is bound to. Both periods reject mimesis in favour of a spiritual or existential encounter. One through religious metaphysics, the other through existential or conceptual metaphysics.

Reformed theologians like Calvin, Zwingli, and others insisted that images distract from Word-based worship and risk idolatry. Iconoclasm was enforced in Protestant regions (e.g. Beeldenstorm in the Low Countries), resulting in systematic removal of statues, stained glass, and altarpieces. Underlying theology: solā scriptūra, priesthood of all believers—no need for intermediaries or sacred representation.

Modern art is not anti-intellectual — it is hyper-rationalised, often requiring linguistic scaffolding (essays, manifestos, accompanying conceptual text) to justify its making. One could call this the Logos without the Mythos: an art that reasons for its individual vision, but does not project an affirmation of shared cultural memory.

We tend to say Modern art is the irrational but fundamentally it's conceptually rational. Over the course of modern history, the figure has gradually stepped out of the artwork into the spectator by the artist’s desire to express subjectivity. With the increasing rationality of the modern age the artist has been driven to explore their art in terms of conceptual thought where eventually the idea is more important than the actual aesthetic of the art. The modern artist distorts the history of art to make their claim for this, saying everything preceding self-expressive Modern art was figurative Classical Art. After the creation of the field of Art History, art across the Modern period divides itself into a great many art movements, but may all be thought of as existential.

Rather than rational art, the drive behind figurative and classical art at its very greatest must have been the irrational creative chaos, the inspired vision, and erotic energy channelled into art. Figurative art can only be made through intense creative energies, abundant sexual energy, channelled into material transformation. Undoubtedly this is why the Italians are so good at it. The aesthetic of this art is a manifestation of their own inner qualities. A projection of the self as external objectification. A cure for the existential experience by affirming the body, the erotic, and the pessimism of one’s own existence by affirming a strong and healthy disposition towards life. Whereas Modern Art depends upon a rational argument in its defensive even being considered art. How can people call Modern Art irrational art when I cannot walk into a gallery of contemporary art without having to read an essay about the work being displayed. Modern Art aiming at the subjective experience therefore has displaced its figurative aspect. Recall that we defined art as the preservation of a disposition of experience. Modern art invites the viewer into their existential experience of life. Into self-investigation of their own existential experience gazing not at illusion of aesthetics but the mechanical process of its tool and making the viewer is to see this as artificiality and not be deceived by the illusion of its ecstatic transformation, to not be taken over by it, and give oneself over to it. The modern artist desires that art be recognized as the work of an artisan. Modern Art soothes its modern viewer because it reflects their own existential feeling. This reminds us of medieval sculptures where the viewer looked into them for absolution.

It resonates their sense of life but that sense of life should be weighed for its value because no other art can prevail today but modern therefore no other sense of life is permitted.

Even when it becomes symbolic (e.g., Kandinsky, Rothko), it is a symbolic search for meaning—not representation of received myths. Modern art is an art without myth. That’s not at all to say an art without religion. Modernity left the church only to find its reflection in the gallery: bare walls, deep silence, and scripture placed beside the frame. Whereas prior cultures emphasised objectivity and polarisation, one of the most dominant sentiments of any art of any field in Modernity is subjectivity and integration. Modern art is not the objective figure in the world, but the viewer in the process of making sense of it.

If we consider Atheism: it's not actually a religious shift. Atheism doesn't constitute the beginning of a new era, but ironically the culmination of Protestantism. Because Protestantism is such an inward-looking religious disposition, seeking secular signals of salvation, embodied in economics and its institutions. From its outset it disassociates itself from the Pope, refuses the use of religious imagery, displaces the church as the centre of the religion, in favour of the eternal-eye on the inner soul of man. Over-time displacing the church into secular institutions. So, if we consider Protestantism to be that radical religious shift, therefore the displacement of the church, which is so vital to Catholicism, is displaced into political institutions and mental states of economic theory, such as diligence, and the prosperity of material wealth as a signals of salvation. It becomes part of a way of living, not so consciously religious as being part of a church as in Catholicism, but in aspects of your secular life. Therefore, because it's so embedded in the foundation of what becomes a Protestant society, it doesn't need the church. We must remember that Martin Luther was enamoured with Saint Paul, otherwise known as Paul of Tarsus, was born Jewish, and was the architect of a Jewish sect called Christianity. His emphasis was man’s inward faith-based path in life, the abolition of ritual in favour of belief, and scripture as a portable temple. Protestantism is the Christian reverting back into the Jew; the internalising of its Jewish substrate. Therefore, if it disassociates the head of the Christian world, places the soul of man rather than the church at its heart, removes religious ritual and mythic imagery, and, emphasises its practices through secular institutions abstracted from ecclesiastical structures; inevitably it removes the need of a conscious awareness of God. Atheism is actually an inevitable culmination of the Protestant ideas. Even Modern philosophy, so dominated by the Germans and French, is really a secularisation of Christianity. Islam, bypasses Christianity, to reemphasis going astray from God’s law as the original imprudence of humanity. Phase five of the Modern era would involved both a disillusionment with the religious ideal of the Modern era, as well as five one of a religious shift belonging to a new cultural period.

PHASE FIVE – DISILLUIONMENT:

If we define Religion as a kind of conceptual thought to make the human experience more agreeable, I personally feel that the most healthy religious attitude and mentality is polytheism. Though Ancient Greek religion was probably the healthiest, most cheerful, and most interesting. Other polytheistic frameworks accomplish a similar end. The plurality of Polytheistic conceptual architecture, doesn't divide the universe into a duality of good and evil but allows for coexisting contradictions, and all aspects of the human experience are deified and into affirmation. I think the human experience is conceptually considered more positive, holistic, in celebration and affirmation of life as it is. I talked through this at length in my video on Ecstaticism.

FURTHER SPECULATIONS

My Four Phases theory rejects the Hegelian dialectic idea of the progress of history, and its notions of synthesis and transcendence. Instead, it posits a Thucydidean and Machiavellian impression of history: that humanity does not change. It rejects the idea of linear history of deterministic progress. Progress depends on the bias of placing value in one place rather than another. Progress cannot be dissociated from ideals. If something moves towards ideals it’s progress; away from, it's decline. Each cultural period seeks the actualisation of its own ideals. Progress would imply all cultural periods aspired to the same ideal; or all artists of all periods trying to accomplish the same thing. They would also have to have perfected the methods of their predecessors, before improving upon their aims by pursuing their own aims. That is not the case. Art doesn’t progress. Each artist is a moment, in a state of self-affirmation, and the discipline of Art History is to contextualise that moment. The chronological history of culture is not driving towards any particular direction, but only towards the ideals of its inauguration, until all variations of its actualisation have been exhausted. During this period, Buddhism and Shinto also underwent a process of syncretism, with many Buddhist deities and Shinto kami being worshipped together.

A refutation of deterministic progress is that such a progress would imply that the powers of the world aspire for progress. When, it’s clear that power aspires only to retain or grow power. Therefore, power endeavours to protect the loss of its power by preparing against anything that threatens it. The future, then, ends up being anything that succeeded which power didn’t prepare for, or underestimated. The future is always something that came from left-field; a phenomenon that no one expected to happen. But was itself an act of self-affirmation. But if you look into why it succeeded it’s because it follows the same aspirations of the ideals of the cultural period, just in a new expression.

Each phase arrives in order, cumulatively rather than merely sequentially. Until the arrival of each next phase, the representing phase of the prior cultural period still hangs over. So, when Protestantism arrived, there was still music styles from earlier times. Then when classical music arrived (which by no surprise is most recognised by German composers) there were still literary styles from earlier times. When the modern novel arrived there were still naturalistic figurative image styles from earlier times. Until those naturalistic images were overtaken by modern art. As the sentiments of the cultural period deepen, the art forms finds ever new and more essential expression of that idealism. Until all aspects of culture are achieving the same end and are exhausted of variations and fulfilment of their ideals. Often leading to disillusionment by the generation who finally receives them, being so far from the religious origin they no longer identify with it.

Let’s talk about endings. An interesting question is why do cultural periods end? A cultural period doesn’t move in a linear direction to ideals but rather prevails against its resistance for a duration of time. There is always an element within culture that undermines the culture. In the case of Ancient Greece, lyrical poetry and philosophy undermined the Homeric traditions, and eventually prevailed over them. In the case of Ancient Rome, arguably without the predominant philosophical school of Neo-Platonism, which was so accommodating to Christianity, such a philosophy wouldn’t have so easily transitioned. The Neo-Pythagoreans saw Plato as one of their own. Neo-Platonism elicits a form of Romanticism, which you can see in all Roman literature which succeeded into the Christian disposition. This is also the problem of the Renaissance The Baroque briefly was in a resurgence of Aristotelian views, such as empirical philosophers like Francis Bacon, Baltasar Gracian, and Ninon de l’Enclos. Yet Neo-Platonic-Christian spirituality prevailed. Whereas, the Aristotelian influence was helpful in undermining the Middle Ages’ Christian spirituality that helped lead artists towards the Renaissance. Hence, Giovanni Boccaccio, who was in the literary phase of his culture, seems to affirm the worldview of later writers of the Baroque who were part of the Counter-Reformation phase one that did not prevail over Protestantism as a cultural direction for the Modern era. Culture is always better whenever it prefers Aristotle over Plato.

Of course, political and economic shifts are a huge factor of cultural change, but I feel the history of economics is derivative of its religious culture. With the economic ethos being merely its religious ethos in practice. Economics is subservient to the religious attitude. Political changes seem due to the degradation or prosperity of a political state, connected to its economic prosperity. Since the images are often a result of the political power and economic prosperity of a state or population it belongs closer to the end of a cultural period rather than its beginning. Politics and economics are derivative of changes which have already taken place. As for scientific developments, science has always thrived in highly religion periods, rather than against them. Scientists also have often been devoutly religious people. The world view of the science is often in parallel to the religious view it thrives within. Therefore like politics and economics, is also a derivative relationship with a cultural beginning, rather than being a catalyst of it.

Culture reaches a point of saturation, not a saturation of excellence, but an actualisation of its ideals, held up by the pillars of a few outstanding representatives. Just as when a meal satisfies our hunger we turn to something else, the culture once satisfied turns to something else. Each new phase is increasingly undermining of the previous. In a sense, the future arises because everything that it wasn't also saturates to a point of expression received as a jolt in religious thinking.

Despite the Modern period being an existential period, not seen since the Middle Ages, its existentialism is not its undoing, but the actualisation of its ideals in the 20th century. Since almost every aspect of Modern world is born out of an ideological viewpoint. Nationalism, Capitalism, Feminism, Socialism, Romanticism, Utopianism, Racism, everything is an ism. Everything is ideological stance. All of them driven principally the naïve optimism of Reason and Science, as a solution to all of humanities incapacities, and once there’s disillusionment about each ideology, the whole thing comes crashing down. Rather than a utopia, this leads us to a kind of dystopia. This disillusionment is Phase Five of Modernity’s cultural period. Post-Modernism, which ought to be called Ultra-Modernism, follows every tenant of Modernity. Post modernism is a continuation of the Ideals of the modern period only more intensely and essential. The dissatisfaction is met with emancipation. Existential despair consoles itself with beauty. But beauty weakens the spirit. In our present age, we are stuck in a cycle of engaging with existential philosophy and then consoling for it with beautiful images, making existential philosophy more accommodating, and consoling for it with beautiful images. The only thing that strengthens the spirit is adversity and love.

GLOBALISATION

Now, people may wonder, for example, if the literature of the Modern period is the novel and that develops out of Protestantism, then why do people write novels anywhere in the world, and why are arguably the best novels ever written by the Russians who are not even Protestants?

My answer is that no matter where you belong in the world, if you adopt a form that belongs to a cultural period's sentiments then you adopt the sentiments that belong to it too. The Protestant sentiments are embedded within the format of the novel. So, anyone who writes a novel absorbs those sentiments simply because the act of writing a novel is also an act of practicing those sentiments. Of course, any region brings their own regional culture into. The Russians perfected the novel on account of that they managed to expand the novel into something philosophical and deeply psychological, whilst also being literary two steps towards poetry, incredibly spiritual, whilst doing everything a novel should. Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Turgenev, Gogol, Lermontov, Pushkin, if you want to count Eugene Onegin. There’s no equivalent except maybe the British Romantic poets. They own their own space within that form.

Similarly, why can a non-Protestant culture like Catholic Mexico have a Frida Kahlo and It be Modern art, or American Jewish painters etc. My answer is that it continues the same Protestant intent: the removal of religious imagery. Modern art is derivative of the Protestant intent. which the Counter-Reformation, led by the Catholic church, responded to by increasing the number of religious images. However, since the northern painters were painting portraits and landscapes, Protestantism effectively introduced non-mythic art. This does not conflict with Jewish or Islamic practice. Therefore, when someone from outside a Protestant region is influenced by what's happening in Modern art then they also absorb those inaugural sentiments. Modern art is non-mythic art interior art. So, as a Modern artist, Frida Kahlo would count as being a non-mythic artist too.

I’ve concentrated on a Eurocentric template. But does this theory apply to non-Western culture? Let’s consider Japan as an example spanning the Kamakura to Tokugawa period (1185–1603)

PHASE ONE – RELIGION:

Zen Buddhism enters from China and Korea during the Kamakura period (1185–1333)— It challenged the prevailing religious practices of the time, particularly the opulence and esoteric complexity of Heian Buddhism. Zen emphasized meditation, self-discipline, and a direct experience of enlightenment. Flourishing in the Muromachi period.

PHASE TWO – MUSIC:

Zen Buddhism’s emphasis on meditative clarity was reflected in the music of this period. The introduction of the instruments like the shamisen ( a three stringed instrumet) and the koto (a 13-stringed instrument) , and a decline in gagaku music. Shōmyō: Buddhist chanting, often performed in a call-and-response style, became an essential part of Zen Buddhist practice. This type of music emphasized simplicity, clarity, and emotional expression. These instruments moved Japanese music away from the older gagaku court tradition and toward a more personal and affective mode of expression, laying the groundwork for musical forms in Nō and later kabuki.) “The Tale of the Heike” Heike Monogatari: recited by lute players, who travelled from place to place, was written in the late 12th century, around 1190. A recited epic, mourning the fall of the Taira clan—reflecting a Buddhist worldview, particularly the concept of mujoˉ (transience). Explores of themes such as the fleeting nature of human life and power. It is often recited by biwa (a type of Japanese lute) players.

PHASE THREE – LITERATURE:

Nō theatre emerged during the Muromachi period, particularly with Zeami's influence in the 14th-15th centuries. No fuses Zen impermanence with samurai aesthetics. A combination of drama, dance, and music, characterized by its minimalistic and poetic style. Performances often feature masks, simple costumes, and a sparse set. The performances are meant to evoke a sense of yuˉgen (profound and mysterious sense of the beauty of the world) and mujoˉ (the transience of life). I’ve explored this artform in my video on Yukio Ninagawa.

PHASE FOUR– IMAGES:

Momoyama art was influenced by Zen Buddhism, which emphasized the importance of simplicity, naturalness, and impermanence. Japanese Ink painting, suibokuga, inspired by Chinese techniques, became popular during the Muromachi period. Artists like Sesshū Tōyō (1429–1508) and his followers created landscapes, often simple yet expressive, that reflected Zen principles of simplicity and the connection between nature and human existence. Zen rock gardens, also known as Japanese dry gardens, are another expression of Zen aesthetics during this period. The gardens are often asymmetrical and minimalist, embodying the Zen ideals of simplicity and the impermanence of life. The Warring States Period saw the development of new artistic and architectural styles, including the use of bold and dramatic designs in temple and castle construction. The period saw significant social and economic changes, including the rise of a wealthy merchant class and the decline of the traditional aristocracy. The period saw a resurgence of interest in classical literature and poetry, with many writers and poets drawing inspiration from the works of earlier periods.

In 1603, Tokugawa Ieyasu established the Tokugawa shogunate, which brought an end to the civil wars and unified Japan under a single ruler. This ends with the Tokugawa period with a resurgence of interest in Shinto, Japan's indigenous religion. The Tokugawa government actively promoted Shinto as a way to unify the country and promote a sense of national identity. The Tokugawa government also developed a new form of Shinto, known as State Shinto, which emphasized the divine right of the emperor and the sacred nature of the Japanese state. This form of Shinto was used to legitimize the Tokugawa regime and promote a sense of national unity. During the Warring States Period, Christianity had been introduced to Japan by European missionaries, and it had gained a significant following. However, with the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, Christianity was seen as a threat to the new government's authority, and it was actively suppressed. In 1614, the Tokugawa government issued an edict banning Christianity.

An artist’s work is never what they consciously sought to do, but what they subconsciously are. People are generally bound to the cultural period they were born into. They stand on a plinth of religious traditions, submerged in the music of their time, overwhelmed by the visual imagery of their age, and absorbed into the literature of their culture. It’s very hard to break out of that. The only way is to see the limitations of each thing and live in that disillusionment of Phase Five, whilst absorbing instead the culture of another period.

The present age presents a compromising problem. We are so inundated with images, which uphold the inaugural ideal, that anything radically different will struggle to thrive. Protestantism ended the Renaissance, the most illuminating era of the past two millennia, overcoming the Counter-Reformation. For a radically new cultural period to emerge, it would be not only from a religious shift, but from an artist to be the philosopher, the musician, the writer, and visual artist combined. What’s more, nothing is more difficult than challenging existing ideas and institutions, that the artist would have to stand on their own independence resources, and sculpt their own culture assertively. So thoroughly would the new have to present itself, that it would need to be appear at both ends.

An analogy of this four phases theory, could be to consider a stone marble block that represents the formal stance of a new worldview. Then the hammer rhythmically hits the chisel against the marble that represents the phase of music. Incrementally, rough implications of human muscle and limbs begin to emerge from the block by the chisel. Finally, a fully formed crystalised of the ideals of that inaugural worldview are manifest. The worldview, the sound, the experience, and the image.

Written by James Dazell (July 2025)

Comments