On Photography

- iamjamesdazell

- Nov 18, 2025

- 16 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2025

“All photographs are accurate. None of them is the truth.”

Richard Avedon

My father was a photographer. An amateur one. He was a chemist and immunologist. He was a managing director of one of the world's major pharmaceutical companies and then set up his own business. But he loved photography. He created the famous logo for the musical Cats with the dancers in the cat's eyes. I would look through his photography books when I was younger to understand the craft. A bygone world in today’s accessibility for novice clickers like myself who take pictures for pleasure of the act. In my student days I really got into photography. My girlfriend model was partly that inspiration though we met through shared artistic interests.

This continued when I worked briefly for AnotherMagazine and i-D magazine. Then record labels Beggars, XL, and EMI. Subsequently, a decade ago, I spent so much of my time at Nick Knight's SHOWStudio. Aside from working within John Emmony's graphic team of art direction, and Nick's work, I loved the team at the time. From Bex Cassie's gallery curation, to my admiration of Lou Stoppard's ability to bring out the intelligence of every participant of her interviews. I got to know Nick. He would read my poetry and watch my earliest poetry films, and on occasion email me some compliments and feedback. He developed a great love for poetry during that time and had deeply considered re-creating the famous Royal Albert Hall poet collective of June 1965 where over seven-thousand people gathered, including Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, and Gregory Corso to read their poetry aloud. He would repeatedly watch the documentary of it called “Wholly Communion.” In fact, the name of my POEMStudio is an affectionate reference to Nick's SHOWstudio. I also became good friends with Joseph Bennett who designed Alexander McQueen's fashion shows after the 90s. I would have dinner at his house, he would show me design books, strange objects he's collected, implore me to watch Tarkovsky films, and even compared my creativity to the late Lee McQueen. The photographer I found most interesting at the time was Craig McDean. Eventually the intoxicating combination of fashion, music, London, I found to be a very dark world, unhealthy, and bad energy and I took myself very far away from it after 2017. I fled to the north and wrote Rewilder which is undoubtedly a reflection of my time in London, and that proximity of the contradictions. In fact, when I translated it into French I didn't recognise it because to me the city of Vale is London and nowhere else.

Nick Knight “Susie Smoking” (1988)

I happened to read some books on photography recently where, though I agreed with many of their statements I couldn't share their conclusions. If Instagram is the summit of what we mean by photography then their statements are true. But considering photography more broadly, I don't think their cynical perspective is the whole picture.

Photography is the most modern of practices. Sometimes history appears to create itself. Hero of Alexandria invented steam power but the Romans were not interested in industrialisation and so it took 1700 years for it to be introduced. Likewise, photo-projection via the camera obscura was invented in the 4th century BC, but the photograph was not created until 1826. History of civilizations don't develop on the invention of things but on the human need for things. The origin of something is very different to the use that it’s put to. The photograph may not have been to the interest of an earlier time than the 19th century. But it was the 20th century that took the practice into an ontological language of its own.

Moving from documenting the world, it was during the simultaneous Surrealist movement, beginning in 1924, that photography began to find its new visual language that broke away from merely following the traditional arts of painting. It was this distortion of reality whilst retaining reality that photography entered its breakthrough phase. This coincided with the invention of the 35mm Leica camera in 1925 which enabled photographs to be taken quickly, in sequence, and spontaneously. This revolutionised photography al di la the very controlled circumstances and long exposure times on bulky glass plate cameras. And with the Leica came the development of a new printing process. Moving away from large format to 35mm negatives, required projecting the negative onto photographic paper. A camera in reverse. I always liked the chemical dark room process; from the pregnant camera to where photographs are born out of liquid in the dark.

Alexander Rodchenko “Girl with Leica” 1933

The fragmented nature of the modern era was the apt cultural epicentre for the photograph to develop and, more precisely, the photographer. Just as the poetry of TS Eliot and other Modernist poets became fragmented so too did the feeling of being in the world; capturing the speed of the world in the chemical industrial reproductive process. The insecure, fragmented, meaningless idea of the world in the twentieth century, combined with the chemical industrial process, was the apt time for photography to fulfil its destined awakening. The photograph ends up a copy of the original negative, reproduced and recontextualised wherever it is shown.

I explained in my essay Four Phases of Culture that a period of images is always the end of a cultural period. Photography exposes this more than any other of the visual practices. A photograph carries the cultural meaning from which it is born. It sits within a meaning that has already been established; within the cultural ethos of its time. We can chronicle the history of the world in panorama, but the photograph can only anthologise history as spectacle, not as meaning. A photograph changes depending on its context. Even if such meaning were possible, it is eroded of relevance with time, and it is time which changes its context. We're so early in the history of photography, we don't know what it’s like for photographs to become truly old. Literature, painting, music, everything gets lost in time, and what gets preserved is merely a mixture of luck and bias.

In the 19th Century, the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé said “everything exists to end up in a book.” Today one could say, everything exists to end up in a photograph.

Steve McCurry “Monsoon” (1986)

Photography and video have become the principal device for participation. It seems unnatural to take a holiday, raise children, or host a wedding without needing a camera. Not to photograph seems as an act of indifference. The photograph, after all, is an imaginary possession of a past, that was itself a fragment and distortion of a real and full moment.

Photography is the art of our time and the internet makes us all billboards of our own lives. Experience has become reduced to something potentially photographable. I think that’s a shame. A photograph is the acquisition of an experience as an object. Or rather the acquisition of a piece, a fragment, of a notion of an experience, distilled as an object. They are captured fragments. They are a most modern practice for that element of fragmentation. An experience is something that happens to you, affects you, changes you. You leave as one person and return as another. Something you feel and be. I love photography, but it’s become too related to experience, and too appreciated as reality.

"What is worth an experience if it is not worth photographing?" Photographs are a kind of certification of an experience. A souvenir of an experience in the way one wishes to remember it. Therefore, an experience is also limited by this very act of photographing. Soon we recall the photograph and not the experience. Stop, take a photograph, move on. Travel becomes merely a strategy to accumulate photographs. Savouring and experiencing then forgotten. Instead, one travels with a work ethic to capture experiences they did not have, and to cover up experiences they wish they didn’t. or would rather not communicate. A photograph is only a piece of an experience. And ultimately to reflect an identity that does not truly exist. In this way, a photograph becomes a costume of reality.

Eve Arnold “Jaqueline Kennedy and her daughter Caroline” (1961)

The photograph is not an image of what exists, but a fragment, designed and distorted, to seem as though it existed. A ghost of the past reappearing in the present. The fragment appears to be complete. It’s this inherent distortion that makes photographers feel they are inherently doing something cool, because they are the “author” of the world they have “arrested” in objectified form. Therefore, the summit of their own canvas of perfection.

“You don’t take a photograph, you make it.”

The photographer, so enraptured by this magical ability to disguise, that they conceal themselves through their own means, to which they bring their subject submissively within that personal world.

Paul Strand “Wall Street” (1937)

I’ve heard it said, to take a photograph is to have an interest in things as they are. Yet that is not true, since to take a good photograph, certain things require enhancing, others distorted, and others entirely left out. Photography is an aesthetic distraction of putting the viewer in a curated relation with the world and therefore, as an authority of redefining its power relation.

What is a bad photograph? Is it not reality as it is? Is it not to have “seen” reality without some stylised subjectivity; to have seen it without pre-interpretation? A “good” photograph is one that presents things more attractive than they really are. Even if the subjects are candid, for photojournalism, the photographer chose and composed the image deliberately.

“Far from an instrument of truth and honesty, that the camera could lie made it more popular.“

Susan Sontag

An artist presents an unreality with the meaningfulness, a truthfulness, of the experience of reality. All art is a means to capture a certain truthfulness in such a way that life is better comprehended and has deeper meaning. Whilst art unmasks reality, a photograph conceals. Ironically, despite its optical limitations, photography is powerful because of what you don't see. Often what makes an image beautiful is by what it lacks than what it shows. Photographs alter our notion of what is worth looking at. Photographs are forced attention by what is subtracted from an image. The photograph focusses attention by losing interest in what is beyond the frame. A photograph inspires us by what it leaves unsaid, completed by the viewer. The extra-photographic image that occurs beyond the composition or the clarity of the image, which appears to us in our minds, projected into the image. The photograph begins a phrase and the viewer completes it.

“There are always two people in every picture: the photographer and the viewer.”

Ansel Adams

As a viewer, the event of a photograph happens when we view it. If a photograph does anything, it reveals the psychological symptom of its author and admirer. I prefer to use the word author for a photographer rather than artist. The photographer is more of a dictator, an authority of their own perception, than a creator per se. The photographer, unlike the artist, intends to reduce, reframe, and isolate to manifest their image. In essence it is a craft of concealing more than they wish to reveal. The artist conversely attempts to reveal.

“A photograph is an encounter; a surprise”

Marc Riboud

There is no war photograph ever taken that compares to Picasso's Guernica. There is a famous book The Gulf War Did Not Take Place (1991) by Baudrillard (connecting this to my essay on Post-Modernism) that means that the war was “experienced” through media images, curated, and distorted, so what images were received was not a reality but a filtered reality through the ideology behind them. As such, all photography is in essence unfree, but bound up with a message its maker wishes to transmit to the viewer. Redefining power relations between viewer and subject. By eliminating distances, the world and people are made to feel more accessible, and simultaneously inaccessible.

There is another factor. The camera relates to the insecurities of the modern world. A good photograph of you is whether the camera likes you. And a good subject is submissive to the authority of the lens. Some people are very unnatural when they have their photo taken because they are trying to find a way to show themselves naturally. For some people, a photographer can take their picture, but they are not there. The camera can't see them. They're revealed by the photograph's missing ingredient: time. They're revealed by their energy, movement, mannerisms, interactions with the world.

Orson Wells gave an anecdote during a 1970s interview discussing stage and the movie actors. Wells walked onto the backstage of a scene being acted by Gary Cooper and, watching his performance, thought ‘oh they’ll have to reshoot this tomorrow: that’s awful.’ But when he saw it played back on the screen, he found it wonderful. Wells says there's no difference between a movie actor and a stage actor. With film, it just depends on if the camera likes you.

Why do people dislike being photographed? Often the same reason they don’t wish their voices to be heard in audio recordings. It redefines self-perception. The camera is an approver. Beauty today is judged by how well the camera likes you. One trusts a photographer who knows their lenses, lighting, and evidence of a “good” photograph because they trust that the camera in their hands will approve them. To the lens, self-approval counts for little. One is often now more attractive because they photograph well, rather than the possession of attractive characteristics.

People used to say the camera steals your soul. The camera doesn't capture you, it has such a magnificent power to create something else of you than what you are. Photography can attract insecure people to its allure precisely because it cannot represent but re-present. It can conceal insecurities of a subject, and it can deliver an illusion of power for its photographer. The photographer manipulates a vision to which others step into its particular gaze. This is as true of actors and directors, as it is of models and photographers. Both want to be shown well, both want to be the dictator of an idiosyncratic vision.

I raised a problem some time ago: how do you photograph intelligence? How do you photograph a person being interesting? Why is it so commonplace, and therefore easy, to capture sexy and cool - qualities which time will erode - rather than cumulative qualities of real value?

W Eugene Smith “Andrea Doria Victims” (1956)

Is that why we enjoy photographs? Does a photograph, as if under the inebriated influence of alcohol, let fall away the deeper, disorderly, and troublesome realities of life, and leaves us staring at a cleansed and less chaotic ulterior reality? A cropped and distorted image of an ideal? An idea of a liberated world, trivialised of inconvenient meaning?

“Photography is a kind of virtual reality, and it helps if you can create the illusion of being in an interesting world.”

Steven Pinker

Photography and video, ultimately create an image-world, which is an artificial world.

“Being educated by images is not the same as being educated by old artisanal images. Photographs, unlike art, are not statements of the world, but miniatures of reality, to appease anxiety, to enhance power.”

Susan Sontag

Given the camera’s association with power relations, there is a predatory element to photography. God knows, more than half the photographers today would give up their practice if they were suddenly forced to only photograph houseplants, toys, and landscapes indifferent to their lens, instead of people willing to be engulfed, and hopefully flattered, by their photographic subjectivity.

George Hoyning-Hue “Swimmers by Izod” (1930)

“To me, photography is an art of observation. It’s about finding something interesting in an ordinary place… I’ve found it has little to do with the things you see and everything to do with the way you see them.”

To the photographer, the world is a canvas of potential. This is wholly different to how a poet is in relation to the world. The photographer is more of a novelist than a poet. Yet the photograph cannot speak. Hence so many place a poem, literary, or philosophical caption beneath their photographs because inherently it carries no meaning. A photograph cannot speak, a photograph cannot explain, they can only acknowledge.

Whereas a poem intends to reveal truth of experience beyond optical limitations, the camera is inherently restricted from penetrating so deeply into experience. It must distort the optical even at its highest potential. In fact, photography may be a medium of distortion and its skill is to find a way for distortion and fragmentation to evoke a truthful moment without being able to actually present it.

“The camera’s ability to transform reality into something beautiful derives from its relative weakness as a means of conveying truth.”

Susan Sontag

The photographer observes their subject matter; the poet absorbs and becomes it. Despite this objectivity the photographer is immensely subjective. It presents the psychological state of its author. The photograph admirer gravitates to images that reveal their own psychological state. The photograph says more about the photographer and viewer than the subject. The photograph doesn't reveal a soul. It cannot see it. Hence once upon a time superstitious people thought the photograph stole their soul.

That is an aspect of why we find photographs and film so compelling. They subtract the clutter of real life and present only the parts we want to see, evoking only the way we want to feel. We envy the world of photographs because they seem without the existential baggage of the world. When really the camera simply cannot receive them.

Photography is inherently a fictious reality. It is an imagined world fused with naturalism, like daydreaming. But it’s this detachment from truth which prevents it from being art.

“Everything always looked better in black and white.”

Jack Lowden

Marc Riboud never aspired to be an artist and was disparaging of photographers who saw themselves in those terms. A photographer is more like a novelist which is why a film director is also more like a novelist. Films were in the beginning very often adaptations of novels because they share the same authoritative lens directing the viewer-reader through their personal vision.

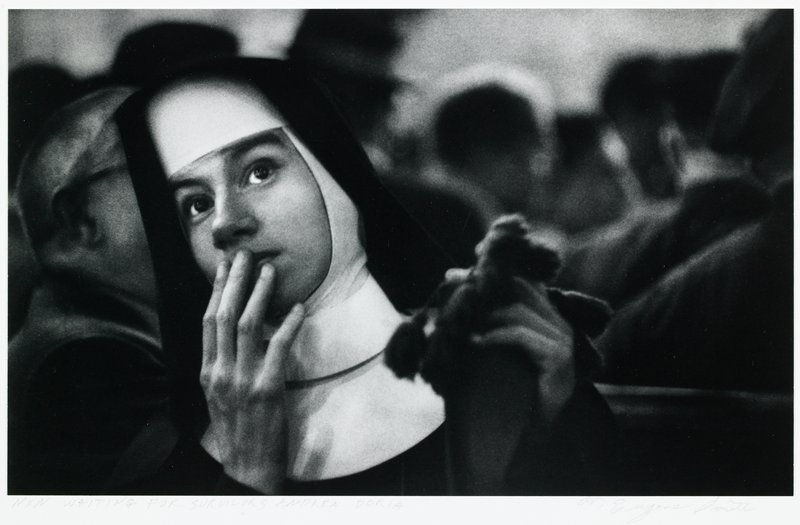

Marc Riboud “Anti-Vietnam Demonstration 1968”

Both of these photographs, by Smith and Capa, are staged compositions but are categorically photojournalism.

W Eugene Smith “A Welsh Coal-Mining Town” (1950)

Robert Capa “Loyalist Militiaman at the Moment of Death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936” (1936)

Cecil Beaton’s work was also often staged. Beaton was fascinated with set design, and he brought these two disciplines together being the set, costume, and photographer for the films Gigi and My Fair Lady.

The photographer wishes to capture and not to reveal, and goes to great lengths to compose, dress, style, and clean their images to have control over what remains hidden and where attention is forced. The photograph doesn't present reality but an ulterior reality. One that we might find more appealing. Not a lie but a detached reality. It's inherently abstracted firstly by composition, secondly by reproduction, and thirdly by the context in which it's subsequently viewed. Like artefacts of African masks in a museum, that are detached from their performative use and are displayed as aesthetic objects.

Composition is a skill of subtraction and abstraction. The eloquence of photography is masterfully excluding and admitting what the author chooses. The ultimate result is to create a powerful image. But what is a powerful image? One that invokes a deliberate thought or feeling. The image cannot speak. The viewer must give it words. It is open to interpretation because it carries no inherent meaning.

“It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.”

Eve Arnold

“A camera didn’t make a great picture any more than a typewriter wrote a great novel.”

To disagree with this, a typewriter does not have the variables of lenses and varied quality of the camera itself that makes an image. If photographers really didn’t believe the camera was responsible for the photograph, they wouldn’t be so condescending towards digital photography. There is a fetish admiration for the film process amongst many photographers. Again, Nick’s influence rubbed off me here too. Nick would use anything to take a photograph. He used iPhones in his studio for some time. It was not about the tools, but how you explore what they can accomplish. There is a power to photography and I believe many photographers explored the form due to its ability to appease their anxiety by the power of its ability to author their own vision. The photograph can hide flaws, because it doesn’t tell the truth, and believes in its discovery of some other landscape. The photographer becomes one with the ability to disguise reality. It intrinsically has the ability to conceal insecurities, and define power relations.

The photograph presents another world. The camera is not a truthful machine it’s an appliance for an art of distortion. If photography is an art it is an abstract art. The camera is a machine of deception rather than perception. Does that demean its creative act? No. Dreams are also fictions. So why cannot a camera be a dreaming machine? They were to Fellini. Not only his Formalism era of film but look at any scene of La Dolce Vita and see how curated and stylised every frame is. Even where to place the camera in cinema, is about defining power relations in order to communicate tone, subtext, relationship, and meaning. Far from realities, like the Surrealists, photographs are fictions. Fictions that resemble truths. Cinema would not be possible as a dreamer’s art if the photograph did not first begin to dream; to fabricate and create fictions of reality.

Sven Nykvist and Ingmar Bergman “Persona” (1966)

Gilbert Taylor and Stanley Kubrick “Dr Strangelove” (1964)

What is better: photography or cinema? Since, when cinema was cinema, it was twenty-four photographs per second. The deep influence of photography has always made cinema look its best.

The French sci-fi film La Jetée (1962) made entirely of photographs.

Photography is an elegiac practice. An almost perverse sensation of both detachment and desire. Cinema adds another element to photography: time. Each frame renders the previous a memory.

My argument is not a cynical polemic against photography. This is not an attempt at an authorative definition of photography but a perspective that merely belongs to a school of thought within photography more broadly. I clearly love photography. But the belief that photography is a means of truth is as outdated as to believe a journalist is a renegade of justice. I believe photography presents fictions, but we have a compulsion to continue to say they are truths. I think this view was also influenced from Nick Knight who was adamant that photography, in the traditional sense, was dead.

Not that I advocate future photography should follow the style of Nick’s photography, but his is a consciously stylised fiction, even his passion for taking photographs of flowers in his garden.

"For me, photography is not an intellectual process, but a visual one. Whether we like it or not we’re in a sensual business”

Marc Riboud

The difference is Nick accepts that it’s fiction. Fictions for effect of delivery. And the images he makes are explorations of that. I remember him saying his favourite model to shoot was Gemma Ward for her otherworldly face. His SHOWStudio expands the image into the dream-like world of film, especially by directors like Ruth Hogben. I don’t think it’s demeaning to say photography is fiction, but rather that we should embrace it. Whenever we tell stories we construct a fiction. But as fictions what can we do with it. I think cinema in the 1960s was at its best when it understood the photograph as fiction. And as such, we should be more accepting of photography's power of myth making.

Me in SHOWStudio in front of Nick Knight’s “Black Rose” (2015)

Comments